The Pygmalion Effect

LIVIU FLOREA

Professor of Management Business

Washburn University School of Business

RANDY EDWARDS

Retired Actuary

A mythological character mentioned in Ovid’s poem “Metamorphoses,” Pygmalion was a Cypriot sculptor who fell so much in love with the perfectly beautiful statue he had carved that the statue came to life.

In a modern variant of the basic Pygmalion myth, My Fair Lady, written by George Bernard Shaw, the phonetics professor Henry Higgins metaphorically ‘brings to life’ Eliza Doolittle by teaching her how to properly conduct herself in social situations.

Borrowing something of the myth, psychologists Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson suggested that teachers’ expectations of their students influence the students’ performance.

Though the research is controversial, Rosenthal and Jacobson outlined a self-fulfilling prophecy in which students, the targets of the expectations, internalize their positive labels, try harder and eventually succeed, confirming their teachers’ expectations.

The two stories about the Pygmalion effect and Rosenthal effect illustrate a psychological phenomenon in which high expectations lead to enhanced performance, while low expectations lead to worse performance. Both outcomes contribute to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The idea behind these stories is that increasing the business leader’s expectations of their employee’s performance, even if not totally accurate, can result in better performance by an employee.

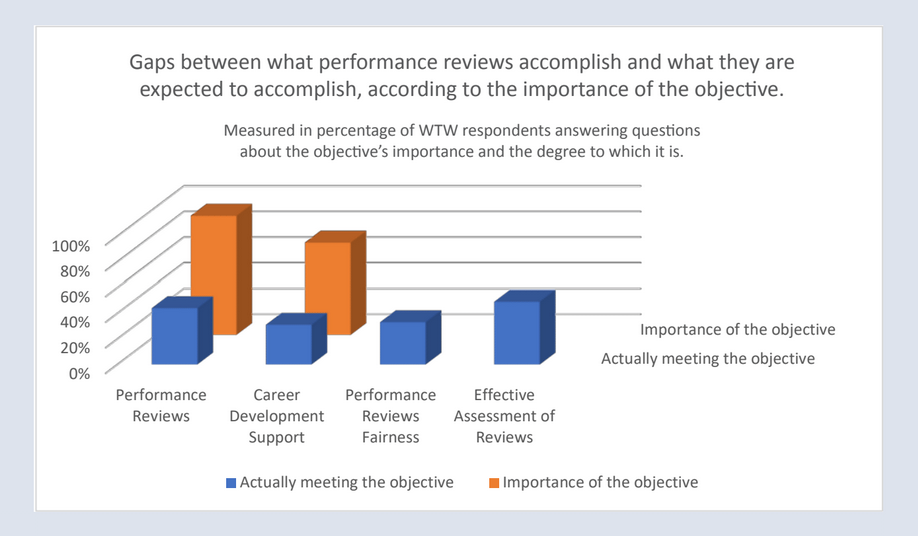

Meanwhile, managers and employees alike see pervasive problems in the performance review process, in the form of significant gaps between what the performance review process accomplishes and what it is expected to accomplish.

Ninety-three percent of North American organizations in the recent WTW (newly re-branded Willis Towers Watson organization) Performance Reset Survey of 837 organizations worldwide, including 150 North American organizations, recognize the importance of performance review for driving organizational performance, but only 44% said their performance management program is meeting that objective. Seventy-two percent said that supporting the career development of their employees is a primary objective, but only 31% said their performance management program was meeting that objective. Only 1 in 3 respondents indicated that employees feel their performance is evaluated fairly, and less than half (49%) agreed that managers at their organization assess performance effectively.

Many employees complain about not receiving feedback on how they could improve their performance and how to further their careers. A 2022 Gallup survey found that 95% of managers are dissatisfied with their organization’s review system. According to the Gallup survey, fewer than 20% of employees feel inspired by their performance reviews.

Likely, the lack of inspiration triggers disengagement, which costs U.S. companies $1.6 trillion a year; that is about $4,900 per person in the US. The performance review problem is exacerbated in the case of Millennials and Gen Z employees who crave feedback and are focused on career development to a larger degree than employees from other generations.

WHY DON’T PERFORMANCE REVIEWS WORK?

One reason is that managers may not have received training for performance reviews and may have been affected by judgmental shortcuts that are associated with less-than-rational decision-making.

Daniel Kahneman, who was awarded Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002, suggested that decision-makers may take judgmental shortcuts to simplify decisions, while Herbert Simon, who received the same award in 1978 argued that people are affected by bounded rationality and satisfice, rather than optimizing or maximizing their outcome decisions.

Additionally, some organizations may standardize the review categories, including very subjective objectives, and apply them to different operating units.

Another reason may be that fewer and fewer jobs have objective and quantifiable outcomes that can be considered a measure of competence, talent or success.

While the performance of a salesperson or knowledge of a professional can be objectively evaluated, attributes such as strategic insight, teamwork potential or innovative thinking can be subjective and hard to review, measure, assess or appraise.

Jack Kelly argues in a recent issue of Forbes magazine that poor review practices mean annual performance reviews and scales composed of employees-rating adjectives should be abandoned and replaced with productive and collaborative approaches that are conducive to open dialogue.

According to Kelly, this change would lead to more meaningful and equitable communication and mitigate the power dynamic between managers and employees.

One reason is that those who review and assess performance may bring their own backgrounds and personalities to bear in the reviews in what is called the “idiosyncratic rating effect.”

An ADP Research Institute researcher suggests that the rating managers bestow on others is more a reflection of themselves than of those they are reviewing.

WAYS TO IMPROVE PERFORMANCE REVIEWS

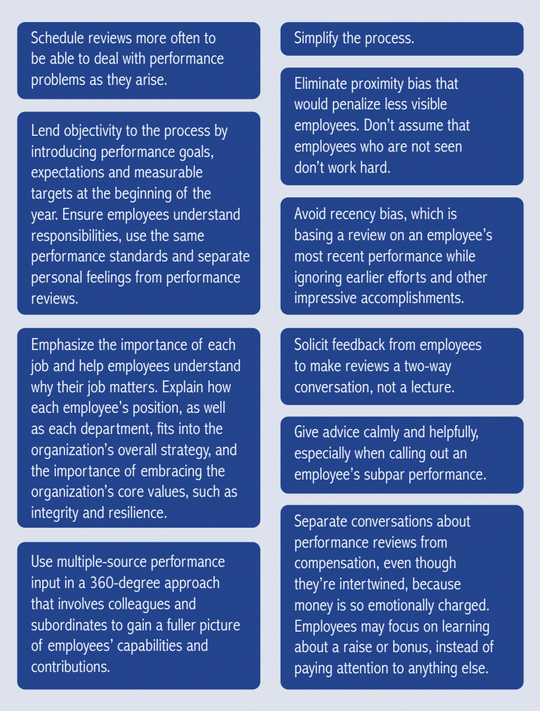

The Spring 2023 issue of HR Magazine that is published by the Society for Human Resource Management, the premier professional association for human resource managers, suggests several ways to improve the performance reviews as highlighted in the boxes to the right.

Not part of this list, but a legitimate way of thinking about enhancing performance reviews is to communicate and build high expectations that can stimulate job performance. Even basic expressions of gratitude have remarkably powerful effects.

Knowing that the manager appreciates an employee’s actions makes that employee feel valued, think more highly of the manager, build quality relationships, work harder because they feel valued and be more willing to increase job performance

WHERE COULD PYGMALION EFFECT FIT IN THIS PICTURE?

Can the Pygmalion effect be an alternative to the broken and unpleasant, but still necessary, performance reviews? To the degree to which it is objective and unbiased, it might.

Gratitude and encouragement grounded in reality are the best ways to make a person feel valued. Regardless of the applicability of Pygmalion Effect in this context, addressing a broken performance review is a priority since many organizations (e.g., General Electric, Google, X, former Twitter) rely on a “stack ranking” system that rates employees on a bell curve and requires that a certain percentage of employees receive low ratings to guide layoff decisions and make employee separation and termination decisions.

While this statistical distribution of results has some appeal, every manager would prefer a group of high performers. Managers can communicate high expectations to their employees by telling them that they have confidence in their abilities and by providing models of good performance.

In summary, the Pygmalion effect can be used as a tool with the appropriate employees to help boost performance. Emphasizing positive employee characteristics and mentioning areas for improvement helps the employee recognize the connection between their performance and managers’ expectations. In fact, there may be times when positive performance is the only feedback to provide to the joy of both the giver and receiver.