The Immigration Debate

The real question is how does immigration truly affect the economy?

The impact of immigration on receiving countries has taken center stage in public debates across the globe. Of particular concern is immigration’s impact on the wages and job prospects of existing workers. Opponents of immigration often contend that large influxes of migrating workers depress wages and job prospects of existing workers, whereas proponents often contend that migrating workers take jobs the economy would otherwise struggle to fill with their presence having a trivial effect on the wages and job prospects of existing workers. The immigration debate is not unique to the United States and Europe, as the conflict plays out in countries throughout the globe. Nor is it a new phenomenon, as the concerns about immigration’s impact on native workers has ebbed and flowed since the mid-1800s. Although not the only factor influencing the debate, the fears that immigration contributes to economic insecurity represents a significant component of the debate. So what does economic theory and empirical evidence inform us about how immigration affects labor markets?

The most apparent impact of immigration on labor markets is the increase in the supply of workers. Elementary economic theory tells us that an increase in market supply results in lower prices, in this case, wages of workers. However, immigration has a second impact on labor markets, as immigrants are both workers and consumers. As consumers, immigrants use their earnings to pay taxes and demand goods and services in the economy, which in turn increases employers’ demand for workers. Thus, immigration has two impacts on labor markets: an increase in both the supply of labor and the demand for labor. As a result, evaluating the impact of immigration on wages depends not on the absolute amount of workers entering an economy, but instead on the relative size of the increases in supply and demand caused by the influx of workers.

In the most elementary analysis, if immigration increases the population by 15%, the economy has 15% more workers and 15% more consumers. Figure 1 illustrates this scenario as supply and demand in the labor market both increase by the same proportion, resulting in no net impact on wages and a proportional increase in the number of jobs in the economy.

In FIGURE 1, immigration has no effect on existing workers, as wages are unchanged and the number of jobs expands to meet the increase in supply. However, the real impact can deviate from this base scenario if immigrants are disproportionately represented in certain labor markets. For example, if economists make up a larger share of current migrants than in the existing population, then the supply of economists would increase by more than the increase in the demand for economists. Conversely, if economists make up a smaller share of current migrants than in the existing population, then the reverse would occur: the supply of economists would increase by less than the increase in demand.

FIGURE 2, shows the impact on labor markets with larger supply shifts. In these markets wages decrease and employment increases by an amount less than the influx of new workers, meaning some current workers would be without jobs in this occupation.

In FIGURE 3, the opposite happens in labor markets with bigger demand shifts. In these markets wages increase and employment increases by an amount more than the influx of new workers, meaning more existing workers become employed in these occupations.

In economics, it is taken as a given that immigration increases overall economic output, as the additional workers are additional economic resources for the economy. In many ways the economic debate centers on the distributional impacts of immigration. Current workers, both native and foreign born, in labor markets like Figure 2 are harmed through lower wages. However, those lower wages result in lower costs for employers that hire these workers and lower prices for their customers. As a result, producers and consumers of goods and services that employ these workers benefit. Similarly, although existing workers in labor markets like Figure 3 benefit from higher wages, the higher costs hurts producers and consumers of goods and services that use these workers’ labor. The biggest beneficiaries in all three scenarios are the immigrant workers themselves, who experience significant increases in their well-being as a result of their migration to the US.

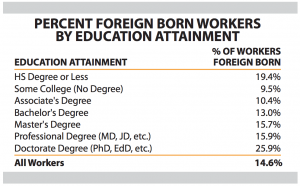

So in light of the theory, what can we presume about the impact in the real world? The table below

Screen Shot 2016-08-26 at 2.22.29 PM

shows the percentage of foreign born workers by educational attainment, which can be thought of as a broad measure of distinct labor markets, taken from the Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey.

By this rough measure of labor markets, workers on the ends of the educational spectrum, those with Doctorates or HS Degrees or Less, compete with more foreign born workers than the 14.6% average, suggesting Figure 2 would be a more accurate model for these workers. Workers with Some College or Associate’s Degrees, on the other hand, face below average competition from foreign born workers, suggesting Figure 3 better represents these labor markets. The proportion of workers with Bachelor’s, Master’s or Professional Degrees that are foreign born are closer to the average proportion for the workforce as a whole, suggesting Figure 1 is more representative of these markets.

What these differences in the proportion of foreign born workers mean for actual wages depends greatly on additional factors, such as how many more (less) workers firms hire in response to lower (higher) wages. George Borjas, a prominent labor economist, estimated the impact of the proportion of foreign-born workers on wages using more narrow occupational categories than the table above. Nonetheless, he found that a 10 percentage point change in the number of foreign born workers was correlated with a 3.7 percentage point decline in wage growth. Based on these estimates, compared to an occupational category with the average number of foreign born workers, one with 19.4% foreign born workers would experience 1.8% less wage growth. Conversely, an occupational category with 13% foreign born workers would experience 0.6% greater wage growth than average.

The issue of immigration can often spur heated arguments with both sides often emphasizing some factors, while ignoring others. When considering immigration’s impact on labor markets, it may be useful to recognize that market forces make little distinction between the sources of additional supply and demand. Whether new workers migrate from another country or from a neighboring state, the impact on labor markets are the same. So whatever one presumes is the impact of an international migration of workers with a particular skill profile on the national economy, one should also presume a comparable impact on a state economy from a migration of similarly skilled workers from other US states. And vice versa.

Paul Byrne, PhD is an Associate Professor of Economics at Washburn University School of Business.