The Economics of Tariffs

For the last year and a half, every week seems to bring more news about the U.S.–China trade negotiations. Signs of possible consensus are followed by news about more trade restrictions, and vice versa. Everyone gets nervous, trying to make sense of what is really going on. Perhaps this is a good opportunity to turn to international trade textbooks and the latest economics research for help in better understanding the current events.

IS FREE TRADE GOOD?

Overall, yes. The decision to engage in specialization and trade is as common-sense as our individual decisions to focus on one primary occupation and then exchange the income from that job for goods and services that other people or entities perform for us. Instead of growing our own food or performing oil changes, most of us prefer to delegate that to a different individual or business. We do this to save time and, considering what we can do in the time we save, such a decision ends up being the least costly one. In economics language, this means achieving the goal more efficiently.

In an exact same fashion, reduction of trade barriers and greater openness to trade increase the set of opportunities for consumers and businesses to achieve their objectives more efficiently. Naturally, this tends to make the nation as a whole better off. There is ample empirical evidence that supports this intuition. This is also the reason why stock market indices, which, in a nutshell, reflect market expectations about future performance of the economy, usually respond positively to any sign of progress in negotiations between the U.S. and China, and negatively to every indication that a new round of mutual trade restrictions is looming. See Figure 1.

IS FREE TRADE EQUALLY GOOD FOR EVERYONE?

Unfortunately, it is not, and this inequality presents itself in more than one way.

First, the flow of cheaper imports that make consumers happy, at the same time hurts domestic industries that compete with those imports. This becomes an issue especially if the burden of trade liberalization falls onto a small group of firms or individuals, making individual losses for members of that group quite substantial. This is one of the reasons why some economists welcome the overall momentum toward freer trade but warn against moving in that direction too rapidly.

Second, the distribution of the overall gains between the two countries engaging in trade is unlikely to be even, either. Once two countries’ businesses see the potential for mutual benefit, they still need to agree on prices of goods that are to be traded. Economics textbooks often leave that decision to the “invisible hand” of supply and demand, but in reality pricing is an outcome of business negotiations, in which two sides are rarely in an equal bargaining position. If, for the sake of an example, multiple competitive importers on one side of the negotiation table face one large (maybe even a state-controlled) exporter, then that large player is likely to negotiate more favorable terms of the deal.

For either of the two reasons, the distribution of gains from trade within a country or among countries is rarely ideal. As many of us vividly remember, the unequal distribution of gains from trade also played a role in President Trump’s electoral campaign.

TARIFFS AFFECT ONLY IMPORTED GOODS, RIGHT?

Wrong. Yes, the U.S. Customs collects the duties only from those goods that cross the border. However, the effects of a tariff extend far beyond that.

In economics language, imported goods and goods produced domestically are “substitutes”. This is a way of saying that, as the price of imports increase due to tariffs, buyers shift toward domestic goods, increasing the demand for them. This, in turn, inevitably pushes the prices of domestic goods up. This pattern persists across a variety of markets and industry structures. In all cases, domestic producers respond to tariffs with higher prices of their own.

ARE TARIFFS BAD POLICY?

As a long-term policy tool – yes. Think of the free trade argument, only in reverse. Any trade restriction may benefit a narrow set of domestic industries, but it always does so at the expense of domestic consumers. Countless theoretical models and empirical studies confirm that notion along with the fact that the overall net effect on the economy of a country imposing trade restrictions is negative. A series of studies published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (ref) estimate that it costs the country more than $500,000 per year to protect one job through trade restrictions.

It is also important to keep in mind that increases in goods’ prices resulting from tariffs reverberate through the entire supply chain. Tariffs on imported steel or aluminum may be lauded by U.S. Steel or Alcoa, but they raise the production costs for automobile and aircraft manufacturers. Those producers will most likely have to pass on some of those additional costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices. According to several independent estimates published recently (ref), tariffs put in place by China and the U.S. would cost an average household between $300 and $800 a year. Simple economics also suggests that because of higher costs of inputs and lower demand for exports, U.S. businesses are likely to experience weaker sales, production cuts, and possibly even layoffs, and we are certainly seeing some of this happening.

As of today, American farmers appear to bear the hardest hit from this trade war. The crop that makes the news most often in this context is soybeans. The official trade statistics in Figure 2illustrates the drop in soybeans trade volumes over the last year, and it does not look pretty. Wheat farmers also took a hit, but a milder one. As Figure 2shows, the volume of U.S. wheat exports to China fell dramatically, but demand from other countries buying American wheat more than made up for that. The federal administration is attempting to mitigate the damage from the ongoing trade conflict by allocating $12 billion in 2018 and $16 billion more in 2019 as farm aid. But, like with any government handout, questions remain about the extent to which this will compensate farmers for losses from decreased sales.

The two biggest exporting industries in Kansas, aircraft and beef, seem to be holding up better, due to the strong demand domestically and the fact that China accounted for only a tiny portion of the overall export sales. Additionally, aircraft and heavy machinery producers were given the opportunity to apply for exemptions from tariffs on steel and aluminum, and many did.This does not intend to imply that problems do not exist. The analysis of the latest economic report by the Commerce Department (ref) suggests that the main factor slowing down the growth in national output in the second quarter of 2019 is a decrease in business investment. This is not surprising: the ups and downs in the United States’ dealings with China cause uncertainty, which makes business owners put off purchases of new equipment and other investments and send ripples throughout the entire economy.

ANY GOOD REASON TO USE TARIFFS?

Most of the considerations listed above suggest that tariffs are bad for the economy. Why, then, did the U.S. administration choose to follow this path? Three possible explanations deserve a mention here.

First, international trade theory argues that tariffs may – in theory – make the country overall better off if the country imposing a tariff is large enough (which happens to be the case of the United States). The argument goes as follows. By raising prices for consumers in the importing country, a tariff reduces domestic buyers’ demand for foreign goods. If the country is large enough, then this decrease in demand would result in the lower world price for the good it is importing. This may partially offset the price increase inside the U.S. and, combined with the tariff revenues for the U.S. budget, may even result in the positive overall effect. This logic makes sense but, unfortunately, two separate recent papers by the National Bureau of Economic Research (ref) found no empirical evidence of such an effect.

Second, recall the argument about the skewed distribution of gains and losses from trade liberalization. President Trump maintains that the U.S. was too generous to other countries in the past, letting them receive a disproportionately large share of the overall benefits generated by free trade. His other claim repeated many times on the campaign trail is that some groups in the U.S. were never adequately compensated for the losses due to trade liberalization, and more likely to get what you want. Clearly, U.S. tariffs hurt the Chinese economy and the retaliation by China hurts the United States. Both sides understand the benefits of free trade they are foregoing with every day of delay. The crucial question is which player in this high-stakes game of chicken can afford to wait the longest.

What to Expect

Some sort of resolution of this tense situation is coming soon. Neither side wants this trade spat to drag out indefinitely. Here is why:

China needs an agreement because the U.S. is a lucrative trading partner due to its huge purchasing power, and also because exports account for 20% of China’s gross domestic product and are an important factor in the country’s economic growth. Prior to the beginning of the trade conflict between the two countries, approximately twenty percent of Chinese exports were sent to the United States.

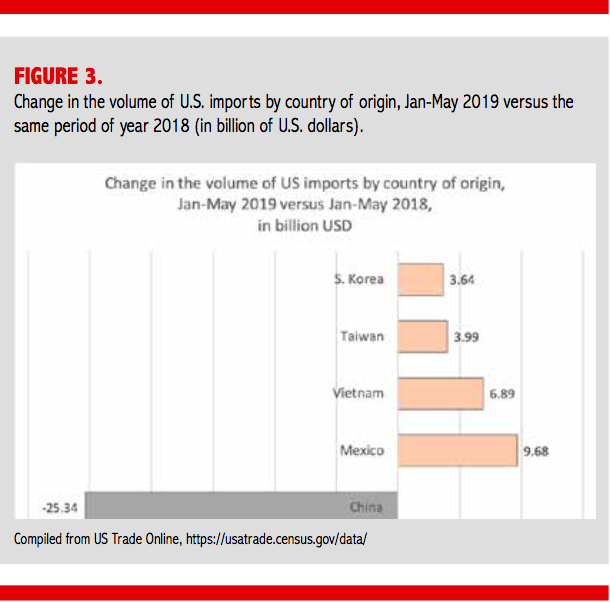

This amount has decreased quite noticeably lately. China has been gradually losing its low manufacturing cost advantage to other countries, not just in Asia. There are signs that multinational companies are starting to move their production out of China. According to the official U.S. trade data (ref), exports of Chinese goods to the U.S. dropped by $25 billion in the first five months of 2019, compared to the same period in 2018, which constitutes a 12.3 percent decrease. That void is being promptly filled by other countries, see Figure 3. The longer this goes on, the larger are the losses for the Chinese economy, not to mention that the process of relocating the factories is extremely hard to reverse.

The United States deals with its own set of time-sensitive issues. The next presidential election is coming up in slightly more than a year, and the economy is an important card in President Trump’s reelection strategy deck. It is no secret that the economy is currently quite robust. However, the Commerce Department reported the 2.1 percent annualized growth rate in the second quarter of 2019, which is lower than in the previous quarter and lower than the President would like to see.

Furthermore, there is every indication that the farm sector, which played an important role in President Trump’s previous presidential victory, would get in real trouble if there is no progress in negotiations and tariffs stay in place for another year. All things considered, it is in the President’s best interest to reach some kind of a deal in the next few months, soon enough to allow the economy to rebound and perhaps add that to his legacy.

The exact terms of the upcoming deal, however, are yet to be seen. In the best case scenario, China will be persuaded to make some concessions the U.S. is asking for. The thing is, even if it does not, some kind of truce will give the President a reason to say he did his best trying to make good on promises made on his 2016 campaign trail.

Let us hope that, once this trade war is behind us, we all find ourselves in a better place than we were before it started. And of course, just like the majority of us, I would like to see the tariffs gone, and I hope they will be.

TK